Feeding the Cuban Insurgents

By Patrick McSherry

Please Visit our Home

Page to learn more about the Spanish American War

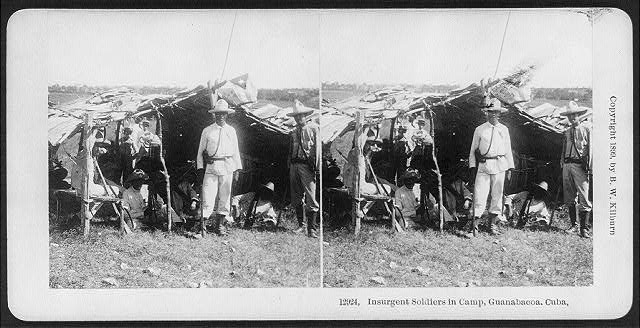

Stereocard

showing a Cuban Insurgent camp

General:

The Cuban Insurgents had to resort to foraging off the land to feed

themselves in lieu of a centralized commissary system. This article

provides information on their most commonly utilized food supplies.

The History:

The Cuban insurgent army under General

Maximo Gomez continually struggled with supplies of all sorts, but

particularly with food. The main reason was that the Spanish Governor

General of Cuba, Valeriano Weyler, introduced

his Reconcentration Plan. Under the Reconcentration

Plan, the Cuban people were removed from their land, with

orders to relocate to central locations and to bring their cattle and any

food supplies they could carry. The goal of the plan was to starve the

insurgents of their supply of men and food. However, the Reconcentration

Plan resulted in untold deaths among the Cuban population and only

partially succeeded in its goal of starving the insurgents.

Additionally, the Spanish military had created a “trocha”during the Ten

Years War and revitalized it by the time of the Spanish American War. The

trocha was in the spirit of the Berlin Wall of the 20th Century. It was a

long 150 to 200 yard wide zone carved across the country with many

fortifications and blockhouses where troops were garrisoned, and who would

guard the strip of land to keep people from crossing over from one portion

of the island to the other. In this way, the insurgents could possibly be

zoned off, reinforcements limited, supplies limited, and insurgent

incursions beyond the trocha alleviated. In addition, the trocha itself

served as a roadway for the rapid deployment of Spanish troops with a

railway line to help facilitate troop movement.

The net effect was that the insurgents were perennially in need of food.

At times, during the war, the Americans did land some rather vast supplies

for the Cuban insurgents, such as through the Tayacaboa expedition.

However, the insurgents had no central supply warehouses or organized

commissary structure. The various commands in the insurgent army took

supplies needed. In many cases, the supplies were taken and carried by the

individual soldiers, and not taken to a centralized depot. That which

could not be carried was left behind or given off to remaining civilians

who were also facing starvation. In a very limited way, Cuban insurgent

commanders could also requisition food from the remaining farmers.

This brought a very limited amount of produce into the Insurgent camps,

but not enough for the men to live on, and not on a reliable schedule.

All of this meant that the Insurgent forces had to forage for themselves,

generally living off the land. An insight into what they lived on and how

they survived is given to us in a book entitled In Darkest Cuba, by N. G.

Gonzalez. Gonzalez was born in Cuba but had emmigrated to the U.S.,

becoming a newspaper editor. He traveled back to Cuba with the Tayacobao

expedition, serving on the staff of General Nunez. With the return of

Nunez to the U.S., Gonzalez stayed behind in Cuba and nominally served on

the staff of General Rodriquez. Gonzalez recorded a day-by-day account of

his life traveling with the Insurgent army and its struggles against

starvation. His account tells of the food sources the insurgents relied

upon.

Foraging as a means of providing food meant that food was not provided

equally to all men, nor was sufficient nourishment provided to any one

man. Also, with so much time spent foraging, less time could be spent on

training, etc. Lastly, should there be an attack, the insurgent forces may

not be immediately available as many men may be out of camp searching for

food.

One major source of food was a rodent known as a hutia. The Cuban hutia,

technically known as “Desmarest’s hutia,” is the largest mammal native to

Cuba, and is also the largest of the twenty-five varieties of hutia.

Gonzalez included many accounts the insurgents, and he himself, hunting

hutia, and cooking them in a variety of ways, from boiling to roasting. He

noted that he “…found it somewhat like squirrel. There was no unpleasant

odor or taste.”

Another major source of sustenance was corn. Ears of corn were gathered in

forging expeditions. Gonzalez described the corn as “…small, yellow and

hard, much of it resembling pop-corn.” The corn was eaten off the cob or

prepared as a porridge or loaf. Gonzalez noted that “Cuban soldiers

[would] punch a piece of tin into a grater, grate the corn off the ears

and afterward wash the floury paste off the cobs so as to save all of the

nutriment; put the paste in a pan and bake, more or less, into a porridge

or a loaf.” Hunger seldom allowed for the substance to be cooked

long enough to form a loaf.

The third key source of nutrition was the mango, of which there are many

varieties in Cuba. Gonzalez reported living off only mangoes for days on

end. He also noted that the juice in the mangoes was beneficial in that,

because of the juice, the troops required less water, helping them to

avoid the often brackish water sources they encountered in their

movements. The mangoes were eaten when ripe or when still unripe without

issue. In spite of the positive recommendation of the U.S. Army Medical

Corps, some Americans, in a belief fueled by information from the

insurgents, thought unripe mangoes to be dangerous to eat, as indicated by

the following:

“They [the

Cubans] call it General Mango, because they say that the mango has

killed more Spanish soldiers than all of their generals put together. If

you eat it, General Mango will kill you…”

Gonzalez reported himself and others eating unripe mangos and not

suffering any ill effects. In fact, chemicals in mangos do produce an

anti-inflammatory effect which may have been beneficial to the ailing

insurgents.

Other lesser food sources included the mamoncillo, a fruit “the size of a

large grape.” The pulp of the fruit was eaten, and the seeds roasted and

eaten. At times very fibrous wild sweet potatoes were found, and fowl of

various types were hunted.

Beef was not available as the cattle had successfully been removed under

the Reconcentration Plan. As a result, the Insurgents, at times, resorted

to eating horse flesh. Horses were a valuable commodity for transportation

by the starving men. However, sometimes horses were still stolen and

butchered, or eaten if they had died of disease. This was an issue since

the disease may have rendered the horse flesh unsafe to eat.

In short, the Cuban insurgents fought against great odds, being not only

poorly supplied with arms and ammunition but also suffered greatly from a

lack of a reliable food supply.

Bibliography:

Lauricella, Marianna, et al.,

Multifacted Health Benefits of Manifera Indica L. (Mango): The

Inestimable Value of Orchards recently Planted in Sicilian Rural Areas,”

Nutrients. May, 2017, 9 (5)

Ledesma, Noris, “Festival celebrates

Cuban Mango,” Miami Herald. July 5, 2016.

https://www.miamiherald.com/living/home-garden/article87682762.html?fb_comment_id=1277500795608606_1277849888907030

Gonzalez, N. G., In

Darkest Cuba: Two Months' Service Under Gomez Along the Trocha From

the Caribbean to the Bahama Channel. (Columbia, S.C: The State

Company, 1922) 168, 178 206-207,

214-215.

“Mammals of Cuba,” Cuba Unbound.

https://www.cubaunbound.com/mammals-cuba

Nofi, Albert A., The Spanish American

War, 1898. (Conshohocken, PA: Combined Books, 1996) 30-33.

Ober, Frederick A., Puerto Rico and its

Resources. (New York: D. Appleton and Company, 1899) 71-72.

Support this

Site by Visiting the Website Store! (help

us defray costs!)

We are providing

the following service for our readers. If you are interested in

books, videos, CD's etc. related to the Spanish American War, simply

type in "Spanish American War" (or whatever you are interested

in) as the keyword and click on "go" to get a list of titles

available through Amazon.com.

Visit Main Page

for copyright data